39848 In-game now on Steam

L4D Art Direction, Part 2: Stylized Darkness

January 2, 2009 - Randy Lundeen

Aesthetics, fiction and gameplay: these are three criteria that we always consider when employing a new art direction for a game. With a game as dark as Left 4 Dead, this meant having to figure out a lot of new ways to use the absence of light to our advantage.

Here's a sample screenshot from an early version of the game.

From an aesthetic standpoint, this is the wrong atmosphere for a horror game. It's too bright. From a narrative standpoint, it detracts from the fiction we're trying to create: if the player's in the midst of a zombie apocalypse, how come everything looks so unaffected by it? Why do all the buildings still look occupied?

Most importantly, though, this screenshot fails from a gameplay standpoint. There are too many light sources to give the player any useful navigational clues. In other words: it's not telling you where you should be heading. Let's look at the same screenshot with simplified lighting:

From watching many playtests, we found players instinctively moved towards well-lit areas. Simplifying the lighting helped the gameplay (the player is drawn to the warm glow down the street, and not distracted by unnecessary light sources); the fiction (this entire city block's been abandoned—something's not right here); and the aesthetics (by simplifying the visual information, we've given a focal point for the eye to follow).

Getting Inventive With Lighting

Left 4 Dead's setting is a post-apocalyptic wasteland just before nightfall. As mentioned earlier, this meant constraints in terms of the light sources we could use without hurting the gameplay, fiction or aesthetics. This forced us to get creative: what lighting would you realistically see in an abandoned city overrun by zombies?

Car headlights are a perfect example. They tell a good visual story, implying a sense of abandonment. When you see a car with its headlights on and nobody around, it's clear something's gone wrong:

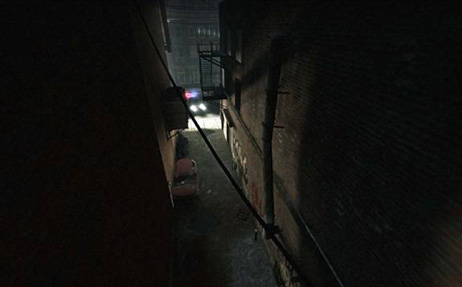

Make that an abandoned police car, and it's clear something's gone very wrong:

On the aesthetic side, car headlights are a low light source. This was a big plus, since it meant a lot of long, dramatic shadows. To help gameplay, we placed the cars at intersections where we wanted to direct players or lead them around obstacles.

Silhouettes

Designing Team Fortress 2 taught us a lot about how important silhouettes are. Clear character silhouettes helped players get distinct reads in an instant, giving them the information they needed to make important snap decisions in a fast-paced environment.

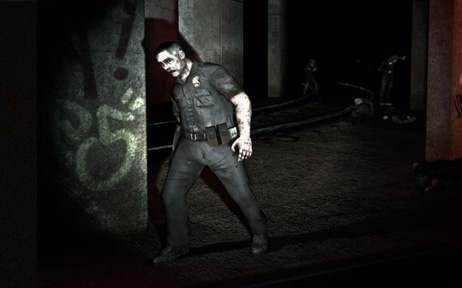

But while TF2 had a bright and colorful art direction, Left 4 Dead takes place in a variety of dimly lit nighttime environments. Because of this, playtesters weren't able to see zombie silhouettes in the midground and background. Because of this, they were repeatedly getting mobbed.

While sudden zombie attacks were inarguably scary, they were also frustrating—players weren't being given the information they needed to react. They wanted that "Here they come!" moment, and we weren't giving it to them. The solution? Light-colored fog:

While not as realistic-looking as actual fog in some settings, it meant playtesters could see attackers in the distance. Once they were able to anticipate attacks, playtesters started to have a much better time.

The Player as Light Source

Flashlights, like car headlights, were a great way to light the game without contradicting the game's fiction. Even better, we found that by making the flashlight weapon-mounted, the light is just slightly off-center at all times. This created interesting shadows and helped make zombie attacks much more dramatic. From a gameplay standpoint, gun-mounted light sources also had the interesting side effect of disappearing when you reloaded or shoved zombies back.

This gave both actions a sense of consequence, and encouraged players to stick close together because they didn't want to be left alone in the dark when reloading.

Self-Shadowed Normal Mapping

Normal mapping is a graphics technique that lets game developers create the appearance of detail on surfaces without additional geometry. Normal mapping could, for example, make a brick wall appear to have depth without having to use a lot of geometry at the sake of performance.

Self-shadowed normal mapping takes this technique to the next level. Not only do the bricks look bumpy-they also cast shadows upon themselves, creating a better sense of realism. Using self-shadowed normal mapping had a dual benefit: It really helped the visuals pop in a game dominated by flashlights and darkness; and, after doing the code work, didn't end up sacrificing any more performance than regular normal mapping.

Specular Surfaces (Wetness)

One final technique that we used in Left 4 Dead was the use of Specular Surfaces, or wetness. In horror movies, you'll find dark settings are almost always wet. Wet surfaces create highlights, they create parallax-they create an atmosphere.

Specular Surfaces worked great with our Self-Shadowed Normal Mapping technique. Wet surfaces imply more detail. Even in a shadowed area, the glint off a wet brick wall implies a greater amount of detail on a surface that would otherwise look blank. Aesthetically, this made environments feel that much more bleak and miserable. Narratively, they implied how decrepit these abandoned areas had become. Wetness also helped gameplay, as a way of counteracting the darkness. In many cases, having a wet surface behind a zombie helped pop its silhouette, just as if it had been standing in front of fog.

We hope you enjoyed this brief look at the thought process behind the art direction in our games, and the importance of playtesting in our decision-making process.

Don't forget to read part one here!